Pakistan’s “Other” Insurgents Face IS

Balochistan is the land of the Baloch, who today see their land divided by the borders of Iran, Pakistan and Afghanistan. It is a vast swathe of land the size of France which boasts enormous deposits of gas, gold and copper, untapped sources of oil and uranium, as well as a thousand-kilometre coastline near the entrance to the Strait of Hormuz.

In August 1947, the Baloch from Pakistan declared independence, but nine months later the Pakistani army marched into Balochistan and annexed it, sparking an insurgency that has lasted, intermittently, to this day.

Now senior Baloch rebel commanders say that Islamabad is training Islamic State (IS) fighters in Pakistan´s southern province of Balochistan.

IPS met Baloch fighters at an undisclosed location in the Sarlat Mountains, a rocky massif, right on the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, and equidistant from two Taliban strongholds: Kandahar in south-eastern Afghanistan and Quetta in southwest Pakistan.

The fighters claimed to have marched for twelve hours from their camp to meet this IPS reporter.

They are four: Baloch Khan, commander of the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), and Mama, Hayder and Mohamed, his three escorts, who do not want to disclose their full names.

“This is an area of high Taliban presence but they use their own routes and we stick to ours so we hardly ever come across them,” explains commander Khan, adding that he wants to make it clear from the beginning that the Baloch liberation movement is “at the antipodes of fundamentalism”.

“Today we speak of seven Baloch armed movements fighting for freedom but all share a common goal: independence for Balochistan,” says Khan. At 41, he has spent half of his life as a guerrilla fighter. “I joined as a student,” he recalls.

The senior commander refuses to disclose the number of fighters in the BLA’s ranks but he does say that they are deployed in 25 camps throughout “East Balochistan [under the control of Pakistan]”.

Khan admits parallelisms between his group and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), also a “secular group fighting for their national rights,” as he puts it

“We feel very close to the Kurds. One could say they are our cousins, and their land is also stolen by their neighbours,” says the commander, referring to the common origin of Baloch and Kurds, and the division of the latter into four states: Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey.

Historically a nomadic people, the Baloch have had a moderate vision of Islam. However, Khan accuses Islamabad of pushing the conflict into a sectarian one.

“Until 2000 not a single Shia was killed in Balochistan. Today Pakistan is funnelling all sorts of fundamentalist groups, many of them linked to the Taliban, into Balochistan, to quell the Baloch liberation movement,” claims the guerrilla fighter, adding that target killings and enforced disappearances are a common currency in his homeland.

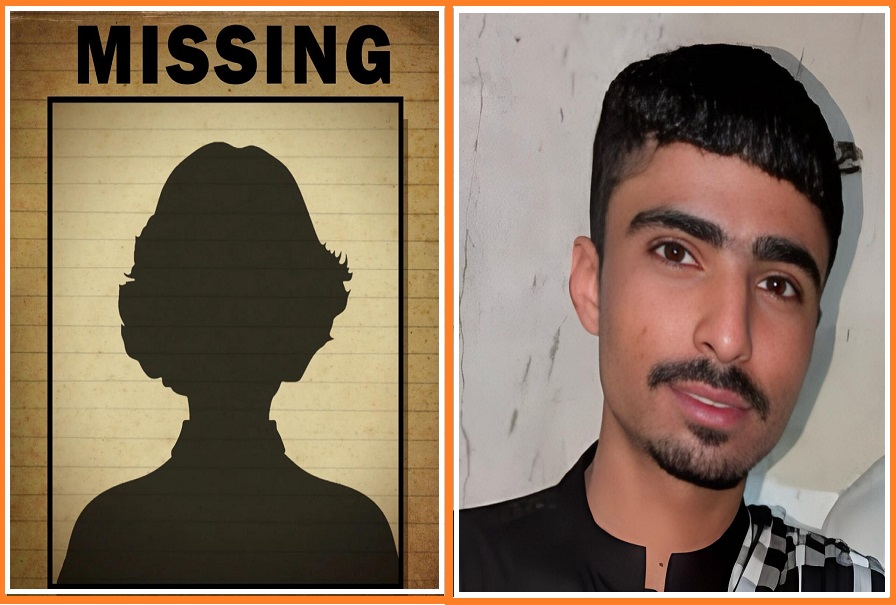

The Voice for Baloch Missing Persons, a group advocating peaceful protest founded by some of the families of the disappeared, puts the number of people from Balochistan since 2000 at more than 19,000, although exact figures are impossible to verify because no independent investigation has yet been conducted.

However, in August this year, the International Commission of Jurists, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch called on Pakistan’s government “to stop the deplorable practice of state agencies abducting hundreds of people throughout the country without providing information about their fate or whereabouts.”

Baloch insurgent groups, however, have also been accused of murdering civilians. In August 2013, the BLA took responsibility for the killing of 13 people after the two buses they were travelling in were stopped by fighters in Mach area, about 50km (31 miles) south-east of the provincial capital, Quetta.

Pakistani officials said they were civilians returning home to Punjab to celebrate the end of Ramadan. Commander Khan shares another version:

“There were 40 people in two buses. We arrested and investigated 25 of them and we finally executed 13, all of whom belonged to the Pakistani Security Forces,” assures Khan, lamenting that a majority of the foreign media “relies solely on Pakistani government official sources.”

Could an independence referendum like the one held in Scotland possibly help to unlock the Baloch conflict? Khan looks sceptical:

“Before such a step, we´d need to settle down both the national and geographic borders as many parts of our land lie in Sindh and Punjab – the neighbouring provinces. Besides, there´s a growing number of settlers and the army is in full control of the country, election processes included,” the commander claims bluntly.

Instead of a consultation, the rebel fighter openly asks for a full intervention, “not just moral support but also a military and economic intervention.”

“The civilised world should support us, not Pakistan. Why help a country that is struggling to feed fundamentalist groups across the world?” asks the guerrilla commander before he and his men resume the long way back to their base.

Balochistan and beyond

The meeting with the BLA leader was only possible via Afghanistan, because Pakistan’s south-western province remains a “no go” area due to a veto enforced by Islamabad.

“The province has the worst record in Pakistan for journalists being killed so local journalists usually censor themselves to avoid being harassed, jailed or worse. Meanwhile, foreigner journalists are deported if they try to access the area,” Ahmed Rashid, a best-selling Pakistani writer and renowned Central Asia commentator, who was an activist on behalf of Balochistan in his youth, told IPS.

The visa ban over this reporter after working undercover in the region was no hurdle to get the viewpoint of Allah Nazar, commander in chief of the Baloch Liberation Front (BLF).

Through a satellite phone, this former medical doctor from Quetta corroborates commander Khan´s statements on a “common goal for the entire Baloch insurgency movement”. He also endorses the BLA commander´s analysis of Islamabad’s alleged backing of fundamentalist groups.

“Pakistan is breeding fundamentalists to counter the Baloch nationalist movement but it has entirely failed. Now they are trying to use the instrument of religion in order to distract attention from the Baloch freedom movement,” Nazar explains from an unspecified location in Makran – southern Balochistan province – where the BLF has its strongholds.

According to the movement´s leader, such threat could well transcend the boundaries of this inhospitable region. Commander Nazar gave the coordinates of “at least four training camps” where members of the Islamic State would reportedly be receiving instruction before being transferred to the Middle East:

“There´s one is in Makran, and another one in Wadh, 990 and 315 km south of Quetta respectively,” says the guerrilla fighter. “A third one is in the Mishk area of Zehri – 200 km south of Quetta – and there are more than 100 armed men there: Arabs, Pashtuns, Punjabis and others who are based there with the help of Sardar Sanaullah Zehri [a local tribal leader]. The fourth camp is near Chiltan, in Quetta.”

Nazar adds that Pakistan’s ISI (Inter-Services Intelligence) is “both activating and patronising the Islamic State.”

“The Islamic State is overwhelmingly present among us. They even throw pamphlets in our streets to advocate their view of Islam and get new recruits,” denounces Nazar.

In October 2014, six key Pakistani Taliban commanders, including the spokesman of Tehrik-e-Taliban – a Pakistan conglomerate of several Pakistani insurgent groups – announced their allegiance to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

“IS is simply an upgraded version of the Talibans and finds sympathy with the ruling establishment in Pakistan,” human rights activist Mir Mohammad Ali Talpur told IPS.

Talpur, who has been challenged and attacked repeatedly for writing about such uncomfortable issues for Islamabad, claims that creating the Taliban is “the core of state policy which has not yet given up on this megalomaniacal scheme of Islam ruling the world.”

Despite repeated calls and e-mails, Pakistani officials refused to talk to IPS. However, the issue is seemingly a well-known secret after the Minister of Interior himself, Nisar Ali Khan, recently told Parliament that even in the naval base in Karachi –Pakistan´s main port and commercial city – there is support for the activities of radical religious groups.

(Edited by Phil Harris)